| . . .Where Gowen Fell. . . Fort Mahone Today |

Throughout the four years of the American Civil War--by rail, by foot, and on water--the 48th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry traversed nearly 5,000 miles of ground, campaigning in several different theaters of operations, and across seven states. Along the way, the regiment had compiled an extensive service record, participating in nearly two dozen major battle actions of the war and in countless other skirmishes and lesser engagements. The 48th's record banner remains emblazoned with such sanguinary and familiar battles as "2nd Bull Run,""Antietam.""Fredericksburg,""Campbell's Station,""Siege of Knoxville,""Wilderness,""Spotsylvania,""North Anna,""Cold Harbor," and "Petersburg," among others.

Yet it was 150 years today--on April 2, 1865--that the regiment fought in its last battle.

For the past 290 days--since mid-June 1864--the soldiers of the 48th remained in the trenches east of Petersburg. It was a severe trial for the men to endure for so long the hardships of life in the trenches, exposed to the elements, and to the constant artillery and musketry fire. It should never had lasted this long; indeed, just a few days after taking up positions east of Petersburg, the 48th embarked upon its effort at tunneling under the Confederate line. Their undertaking was remarkably successful and it should have led to the end of the siege at Petersburg. If only Meade and Grant and Burnside had handled things differently. Surely not a day went by after the bloody repulse at the Crater that the men of the 48th thought about what could of been; how they should have been at home by now; how they should have been the architects of the grand Union victory. Frustration, even anger and resentment, remained.

Yet with the arrival of spring in 1865, there was a sense that, at long last, the end was near. As regimental historian Oliver Bosbyshell noted, "As the spring came on all felt that decisive action would surely ensue." In early March, Lincoln had taken the Oath of Office for the second time while, further south, Sherman and his men were cutting their way through the Carolinas. And at Petersburg, Grant decided that the time had come to strike again at Robert E. Lee and his vaunted, once seemingly-invincible Army of Northern Virginia. During the final days of March and into April, Grant directed his army to extend to the left, toward Lee's right flank and rear. There was a series of running fights, skirmishes, and pitched battles, all of which ended badly for Lee; his lines were stretched far too thin--his army was on the verge of its breaking point. He knew Petersburg and Richmond must surely fall. On April 1, Union forces under Philip Sheridan and Gouverneur Warren won a marked victory at the Battle of Five Forks, inflicting nearly 3,000 casualties upon Lee's ever-dwindling army and, perhaps more importantly, opening the way to sever Lee's only remaining supply line, the Southside Railroad. When Grant learned about this, he knew the time had come; Lee would be desperate. Grant therefore decided to order an all-out assault on the Confederate lines immediately east and south of Petersburg. To carry out this assault, he called upon his Sixth and Ninth Corps.

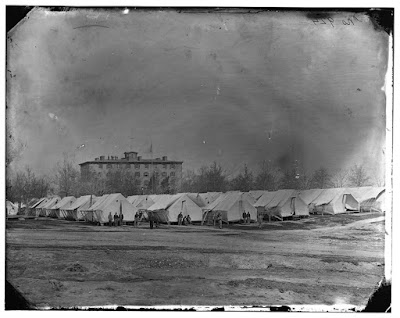

The 48th Pennsylvania Infantry formed part of General John Curtin's brigade, in Robert Potter's division, of the Ninth Army Corps, which, since the previous August had been under the command of Major General John Parke. Late on the night of April 1, Parke received orders that he was to attack. He opted to launch the attack directly from Fort Sedgwick--which the men in blue had dubbed "Fort Hell"--and directly upon the Confederate fortification known as Fort Mahone, better known as "Fort Damnation." The Confederate numbers had thinned considerably there, but their defensive line--and especially Fort Mahone--was still quite imposing and formidable. It would be a desperate and deadly struggle, with the men forced to charge across that no-man's land that separated the opposing lines of earthworks and fortifications, broken by abattis and chevaux-de-frise, in the face of a deadly storm of lead and iron. This open, deadly land between Forts Hell and Damnation the men called "purgatory."

|

| April 2, 1865 Petersburg The 9th Corps's Attack is on far right of map (Map by Hal Jespersen, www.posix.com/CW) |

On the night of April 1, the soldiers of the 48th learned of their orders. Their commander--Colonel George Washington Gowen--had been summoned that night to General Curtin's headquarters and there Curtin explained the plan to storm Fort Mahone directly to Gowen and to all of his brigade's regimental commanders. At the end of their meeting, after all arrangements were made, Curtin shook hands with each of his regimental commanders. Gowen, who had taken command of the 48th upon Henry Pleasants's departure in December 1864, was well acquainted with Curtin and as the two shook hands, Gowen reportedly told Curtin that the attack on Fort Mahone would be his last battle, that he had a sense that he would not survive the coming storm. Curtin attempted to disabuse Gowen of this idea and told him that he would place the 48th in reserve. But Gowen objected and insisted that he and his hard-fighting, veteran regiment take their designated--and rightful--place in line.

Meanwhile, the soldiers of the 48th were maneuvering in the darkness, eventually taking up position to the left of Fort Hell. In their haversacks they carried three days' rations, consisting mostly of sugar, coffee, and hard bread, remembered Sergeant William Wells of Company F. Although it was spring, it was still early enough in the season for the nights to be rather cold and the recent rains had turned much of the trench lines into muddy pits. And so, exposed to the chilly air and with their boots and pants damp and covered with mud, the soldiers of the 48th, having arrived at their designated jumping-off point, broke ranks and. . .waited. Surely a strange mix of foreboding and relief coursed through the regiment that night, with the usual anxiety and fear that came before any big fight but this time tempered by the thought that this might just be the battle that at last ends the war. One more battle, one more fight. . .then they could finally go home. No doubt the thought of loved ones back at home filled their thoughts as the men waited for the inevitable orders to attack. Through the darkness some of the men may have strained to see their objective, Fort Mahone, looming like a dark shadow before them, only a few hundred yards to their front. To their right, on the other side of Fort Hell were the men of Hartranft's Third Division, Ninth Corps, also awaiting the orders to advance; at the same time, to their left, further to the south and west, soldiers of the Army of the Potomac's veteran Sixth Corps were also taking up positions.

To better their chances, Grant decided to precede the infantry assault with all-out artillery bombardment. Throughout the night of April 1, the artillerists manning the cannons all along the Union lines east and south of Petersburg prepared for what would be a massive and memorable artillery barrage. As they wheeled their guns into position--and as the gunner's adjusted their elevating screws and got good range--an eerie silence descended upon the lines. It was already past midnight; Sunday, April 2 had dawned. Few got any sleep that night; many may have tried but the anxiety was much too pronounced. Most of the men were lost in their thoughts. For the moment, in the dark, in the trenched, all was quiet. Then, suddenly, a lone voice rang out. A soldier, described as "some irrepressible Irishman from Company C" shouted for all to hear, "Boys, we're going to early mass." This broke the tension and "caused the boys to laugh," remembered one veteran, "when they did not feel much like it."

It was not long after this that the artillery opened fire and it would be an experience the soldiers of the 48th would not soon forget. Joseph Gould, regimental historian, later recalled that "Orders had been issued on the night of the 1st that all batteries on the line should open their guns to cover the advance of the infantry. The roar of the signal gun at the Avery house found all the artillerymen at their posts and anxious to end the war. The bombardment grew furious as it increased along the whole line, from north of Petersburg to Hatcher's Run. The rebel guns replied with vigor, and this bombardment was the most terrific experienced on that front. The sight was one rarely seen. From hundreds of cannons, field guns and mortars came a stream of living fire as the shells screamed through the air in a semi-circle of flame, the noise was almost deafening." The men marveled at the sight, awed by the shells streaking light and flame across the dark night skies; no doubt the ground under them trembled. The bombardment was to last until 4:00 a.m., when the infantry would then charge forward. . .but at 4:00 o'clock it was still so dark that the men would not be able to see. The assault was delayed another half an hour, while the artillery barrage resumed.

Then, at long last, came the appointed time. . .at 4:30 a.m., orders raced their way along the soldiers in blue. The men rose to their feet, stretched their legs and quickly fell into line, taking deep breaths and wiping the sweat from their palms. Potter's division of the Ninth Corps, which would lead the attack from the left of Fort Sedgwick while Hartranft's men attacked on the right, took up position, stacked up and stretched out eighteen-regiments deep. Making their way forward, the regiment passed around the rear of Fort Sedgwick, through trenches that were muddy and, in places, nearly knee-deep with water. Making their way across the Jerusalem Plank Road, the battle lines were formed and through the misty fog of that fateful dawn, the men began their charge forward.

|

| Alfred Waud Depiction of the Ninth Corps's Attack on Fort Mahone (Harpers Weekly) |

Gould wrote that that morning the soldiers of the 48th were "eager to be avenged for the repulse at the explosion of the mine eight months before." Very succinctly he recorded that the men "fought like demons; and, in the teeth of the storm of grape, canister and musketry, plunged into the field and charged without flinching, until they reached the inside of the enemy lines." The fields over which they advanced were swept with a destructive fire but it took only a matter of minutes before the 48th made their way across "purgatory." Their advance was soon stalled, however, when they reached the Confederate abattis and cheaveux-de-fries immediately in front of Fort Mahone. One man, known only as "R," wrote that confusion ensued when the necessary halt was made in order to remove these obstructions and during this confused halt, "the enemy poured a destructive fire both from infantry and artillery" upon the stalled 48th. "Here the regiment was massed," recorded Sgt. Wells, "seeking a passage and forcing their way through as fast as the pioneers cut away the obstructions." The pioneers, who led the way with their axes, worked feverishly to cut through the abattis and cheaveaux-de-fries, but with each passing moment, men were falling. Sergeant Patrick Monaghan later declared that here, the "regimental front was rapidly diminishing." In the dirt and mud, in the damp mist of that early April morning, all was chaos, madness, slaughter. . .

|

| Surgeon William R.D. Blackwood (center) Library of Congress |

In the midst of this, William Robert Douglass Blackwood, the regimental surgeon, was conspicuous in his bravery. As the action raged the hottest, twenty-five-year-old Blackwood, a native of Ireland and graduate of the University of Pennsylvania Medical School, made his way repeatedly to the front to help remove severely wounded officers and soldiers from the field, all while under a heavy fire from the enemy. Thirty-two years later, in July 1897, Blackwood's most distinguished gallantry at Fort Mahone would earn him a Medal of Honor.

|

| Blackwood Removing Wounded From The Field From Deeds of Valor |

Meanwhile, at the front, the attack bogged down; the 48th still stalled in their advance. Alongside the regimental colors was Colonel George Gowen, waving his sword and shouting encouraging words, doing all in his power to keep the men moving forward. But it was at this moment that Gowen's premonition came to fruition. Monaghan--whose braver at Petersburg the previous summer earned him a Medal of Honor--remembered seeing Gowen lean over to talk with Sgt. Samuel Bedall, who was carrying the flag. Gowen then "straightened up" remembered Monaghan, "when a shell, hot from the mouth of one of the rebel guns of Fort Mahone, exploded in our midst." Gowen instantly fell forward, directly on his face and when Monaghan turned him over he discovered that half of Gowen's head had been blown away. Indeed, Gowen's blood and brains were splattered on the flag carried by Beddall. Along with two others, Monaghan carried Gowen's lifeless body back to the captured Confederate picket lines further to the rear.

|

| Colonel George Gowen Killed in Action April 2, 1865 |

In this initial charge, only a handful of soldiers actually made it to within the earthen walls of Fort Mahone. Perhaps seeing Gowen fall inspired them to keep going; either way all who did were either gunned down or captured. Most of the regiment fell back to reform. While there, General John Curtin, the brigade commander, made his way into the ranks of the reforming 48th. Exhausted, Curtin, a fellow Pennsylvania, leaned upon his sword and called out, "Let us make one more charge for the honor of the Old Keystone State!" And around him, the 48th gathered. Curtin turned to Sgt. Wells and to Corporal Howard Haas of Cressona and asked them to find the colors. Soon, Wells and Haas returned with Sergeants Beddall and William Taylor, "two of the best and most gallant men in the regiment," said Wells. With this nucleus formed, said Wells, the soldiers of the 48th, "without much regard to Company formation," soon charged back across purgatory and toward Fort Mahone. The soldiers "advanced with loud and continuous cheering to the assault, determined to avenge Colonel Gowen's untimely death. Over, around, and through the remaining obstructions with wild shouts they fly, and over the moat, already filled with dead and dying, they reached the glacis of the fort, and, muzzle to muzzle, patriot and rebel, blaze into each others faces, the guns in the fort being now useless."

|

| Sergeant Samuel Beddall, one of the youngest soldiers in the regiment, carried a flag during the Attack on Fort Mahone (From Gould) |

|

| Sergeant Patrick Monaghan Removed the Lifeless Body of Gowen from the Field |

|

| Sergeant William Wells Wounded During Final Stage of Battle (From Gould) |

The 48th poured up and over the walls of Fort Mahone. Nearby swept forward the 39th New Jersey Infantry. Captain John Williams of Company F was fearful the 39th's flag would be captured and so shouted out, "Forward, boys, and save the Jersey colors!" With one more determined push, the 48th swept through Fort Mahone. "Hand to hand, butt to butt, bayonet to bayonet the fight continued," said Wells. It was not long before the Confederate line broke, the men fleeing to the rear. Fort Mahone had been taken. The 9th Corps's attack, however, soon bogged down in the maze of entrenchments behind Fort Mahone. They would struggle to hold onto their foothold, for Confederate General John Gordon would spend much of the rest of that Sunday launching determined counterattacks to wrest Fort Mahone back from the boys in blue. Further to the west, however, the soldiers of the Sixth Corps enjoyed greater success in punching through and routing Lee's men from their entrenchments and later that evening, a defeated Robert E. Lee ordered an all-out evacuation of Petersburg. The ninth-month-long siege was at last over.

| Modern-Day Image of the Location of Fort Mahone The Monument of the 48th Pennsylvania pictured here was placed near the spot where Gowen Fell |

150 years ago today, on Sunday, April 2, 1865, the 48th Pennsylvania Infantry fought its last battle of the Civil War. They had succeeded in breaking into Fort Mahone and driving the Confederates from this formidable position but the regiment had paid a dear and heavy price. In the aftermath of the fight, it was recorded that eleven men--including Colonel Gowen--were killed or mortally wounded in the assault, with another fifty-three men wounded, and twenty-one either captured or missing. Several of the wounded would later succumb to their injuries, bringing the total fatality count up to sixteen.

|

| Private Daniel Barnett Co. E Killed 150 Years Ago Today At Petersburg (Hoptak Collection) |

The casualties sustained by the 48th 150 years ago today, in the regiment's final battle of the war--the Assault on Fort Mahone at Petersburg--follows:

Killed/Mortally Wounded: (16)

Colonel George Gowen

Sergeant John Homer, Co. B

Nicholas Stephens, Co. B

John Coutts, Co. B

Cpl. James Nicholson, Co. C

Aaron P. Wagner, Co. D

Daniel D. Barnett, Co. E

David McElvie, Co. F

James King, Co. H

William Donnelly, Co. H

George Uhl, Co. H

Albert Mack, Co. I

Albert Zimmerman, Co. I

Wesley Boyer, Co. I

Jacob Reichwein, Co. I

Simon Hoffman, Co. K

Wounded: (53)

John Adams, Co. A (slightly, in foot)

1st Sgt. John Watkins, Co. B (severe, in thigh)

Sgt. Robert Campbell, Co. B (slight, in wrist)

William H. Ward, Co. B (slight, in thumb)

Robert Jones, Co. B (severe, in face)

George Seibert, Co. C (severe, in head)

Casper Groduverant, Co. C (slight, in shoulder)

Albert Kurtz, Co. C (severe, in thigh)

James F. Martin, Co. C (slight, in finger)

Paul Dehne, Co. C (slight, in hand)

Sgt. Henry Rothenberger, Co. D (severe, in eye)

Cpl. Levi Derr, Co. D (slight, in foot)

Jacob Schmidt, Co. D (severe, in head)

Jacob Schmidt, Co. D (severe, in head)

Edward McGuire, Co. D (slight, in finger)

Joseph Buddinger, Co. D (slight, in shoulder)

Chester Philips, Co. D (slight, in shoulder)

Thomas Wische, Co. D (slight, in head)

Cpl. William Morgan, Co. E (slight, in leg)

William James, Co. E (slight, in arm)

Robert Meredith, Co. E (severe, in right knee)

Frederick Goodwin, Co. E (severe, in right hand and neck)

Thomas Hays, Co. E (slight, in wrist)

2nd Lt. Henry Reese, Co. F (slight, in arm)

Sgt. William Wells, Co. F (severe, in shoulder)

Cpl. John Devlin, Co. F (severe, in hand)

James Dempsey, Co. F (severe, in leg)

John Crawford, Co. F (slight, in leg)

Peter Bailey, Co. G (slight, in hand)

John Droble, Co. G (severe, in right shoulder)

Patrick Daley, Co. G (slight, in finger)

Nicholas Fers, Co. G (severe, in left thigh)

Thomas Howell, Co. G (slight, in abdomen)

Thomas Smith, Co. G (slight, in thigh)

John Wright, Co. G (severe, in thumb)

George Kane, Co. G (severe, in leg)

1st Lt. William Auman, Co. G (severe, in mouth)

Sgt. Peter Radelberger, Co. H (severe, right arm and breast)

Willoughby Lentz, Co. H (slight, in shoulder)

George E. Lewis, Co. H (slight, in thigh)

Benjamin Koller, Co. H (slight, arm)

Cpl. Henry Matthews, Co. H (slight, in arms)

2nd Lt. Thomas Silliman, Co. H (severe, in throat)

Jonathan Mowery, Co. I (severe, both thighs)

Charles C. Wagner, Co. I (severe, right leg)

Joseph Shoener, Co. I (severe, right leg)

John Road, Co. I (severe, right leg and wrist)

Henry Goodman, Co. I (dangerous, in face)

Benjamin Kline, Co. K (slight, in back)

Paul Snyder, Co. K (slight, in back)

Jacob Ebert, Co. K (severe, in thigh)

David Philips, Co. K (slight, in side)

Jno. Williams, Co. K (slight, in arm)

Joseph Wildermuth, Co. K (severe, right shoulder)

Captured/Missing In Action: (21)

Sgt. Isaac Fritz, Co. B

William Reppert, Co. B

Michael Kingsley, Co. B

Lewis Kleckner, Co. B

Henry Rinker, Co. B

Daniel Hurley, Co. B

Cpl. James Hannan, Co. C

Samuel Kessler, Co. D

1st Sgt. John McElrath, Co. E

Cpl. George W. James, Co. E

Daniel McGeary, Co. E

John O'Neil, Co. E

Patrick Galligan, Co. F

Sgt. James McReynolds, Co. I

James Mullen, Co. I

Theodore Pletz, Co. I

John Oats, Co. I

Thomas J. Reed, Co. I

William Pelton, Co. K

John Marshall, Co. K

George Showers, Co. K

*Information from Joseph Gould, The Story of the Forty-Eighth, Oliver Bosbyshell, The 48th In The War, and Stu Richards, http://schuylkillcountymilitaryhistory.blogspot.com/2009/09/last-assault-of-48th-pennsylvania.html

.jpg)